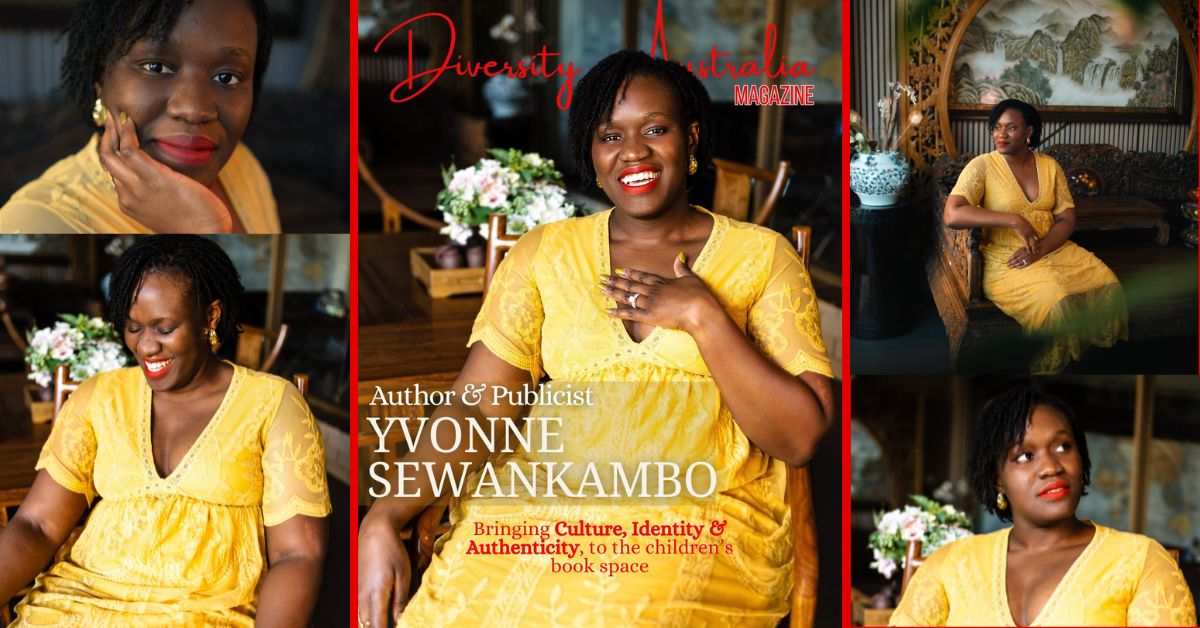

DAM: We first met Author and Publicist, Yvonne Sewankambo, a few years back; one of our founders was speaking at an event on the lack of Representation in Australian media and the difficulty of being one of the first to challenge it, to which Yvonne raised her hand and matter of factly agreed, ‘I’ve been there too’. Sitting down with Yvonne, it’s clear that her passion for authentic storytelling that helps the multicultural children growing up here feel seen, heard and celebrated – is embedded in her work. In this cover issue, we speak with Yvonne on her family and upbringing in Uganda, how a difficult time during Covid led her to becoming an Author of children’s books (‘Good Hair‘ & ‘First There Was Me, Then There Was You’), and her latest work, ‘How My Family Says, I Love You’, which delves into the many ways families from different cultures show love without actually saying those three words.

DAM: Yvonne, tell us a bit about your upbringing.

YS: I grew up in Uganda, which is a tiny but beautiful country in East Africa. My childhood was surrounded by family, which was a big part of growing up. I have an older brother, but I constantly had my cousins and my extended family around me from weekends to school holidays, so we often had bunk beds and mattresses on the floor. It was a beautiful chaos we were in. We’d go and visit my grandma and grandpa (my paternal grandparents who lived less than a 10-minute drive from us) every other weekend at a minimum. We’d call our cousins and say, “We’re going to grandma and grandpa’s, are you guys coming?” And then they’d try to convince their parents to go too. We’d spend the afternoons running around and playing, and making memories.

DAM: That’s beautiful.

YS: One key thing I remember so fondly is our dining table, because everything happened around the dining table. I just remember it being this place of laughter, fun, teasing, whatever it was, and I think of it very fondly. My dad had to move recently and he had to get rid of the dining table. All I remembered were the memories that kept flooding back. Thinking of all the chaos my cousins and I, even my friends, got up to, just around that table.

“Everything happened around the dining table. I remember it being this place of laughter, fun, teasing, whatever it was, and I think of it very fondly… Growing up, you never had to make an appointment to see family. If you came to stay and tried to leave before dinner it’s like, “No, no, no, you cannot leave without me feeding you”.”

yvonne sewankambo

Growing up, you never had to make an appointment to see family. You’d show up; it didn’t matter what they were doing. They might be stressed that you just showed up, but they will never turn you away, and they will make you a full meal, or they will add you to the dinner plans. If you came to stay and tried to leave before dinner it’s like, “No, no, no, you cannot leave without me feeding you”, because they’re like, “How dare you come to my house and I don’t feed you? What if someone else hears that you came and I did not give you any?!”

DAM: That’s very true of Ethnic families!

YS: It was very hard adjusting to life outside of that, like here (in Australia). It’s like, ‘We’ll see you this day, this time’, and it’s usually a two-hour window because everyone else has other plans. To me, it’s very common that you don’t kick people out unless you genuinely have something to go to. I wish I could replicate something like that here in Australia for my son. Maybe I’m just going to have to build the biggest community that I can.

DAM: Definitely. Speaking of family, did your parents support your career aspirations? Did you always want to be a writer?

YS: So both my parents are doctors which meant growing up, we were surrounded by doctors; that’s all I knew. I was a smart kid in school, top of my class, so I also assumed that I would be a doctor. I remember being a kid and when people would ask me, ‘what do you want to be?’ I’d say a doctor, without understanding what that really meant. As I got older, around 14-15, I started to question if that’s what I really wanted to do. My dad’s a lecturer as well as a researcher, so over the years, he’s seen students in his classrooms who should and shouldn’t be there. Not in a bad way, that they don’t have the ability, but they just don’t have the passion. And I feel like with certain careers, medicine being one of them, you really need that drive and passion because on the hard days, that’s what’s going to help you through it, especially since you are in charge of people’s lives. I realised I actually had no love for it and I instantly knew I wasn’t going to do it. But then I didn’t know what I wanted to do. The other options were – nursing? No. Engineering? No. Law? No. It’s just going down the list of, you know, the “ideal” careers. I was really good at math, I genuinely enjoyed it, I still do, so I did my undergrad in statistics. I loved numbers and the research that went into it. Then, I think after the first month, I knew it wasn’t for me. Being in a room and just surrounded by numbers sounds great but it wasn’t fulfilling for me.

“What I actually enjoyed was listening to and understanding people’s stories, but again, I didn’t have the writing in the back of my head at all because I didn’t know any writers.”

yvonne sewankambo

DAM: And was it always in the plan to move abroad?

YS: I came here [Australia] to do my post-grad. One of my friends who was training to be a journalist at the time said, “You’re actually really good at managing situations and organising events”, and I was like, what does that mean? She suggested I look into something that taps into that. I looked into PR and events because they went hand in hand, and I was like ‘this actually sounds like me’. So I thought, I’m going to do that for post-grad, do a year so that I can get that degree under my belt, but in that year, I’ll do as many internships as I can because I’m up against people who’ve done a bachelor’s in communications in their undergrad. That was what led me to get an internship, which turned into a full-time job, and I’ve been doing PR ever since.

I was just drawn to telling stories, which PR is – it’s telling other people’s stories but you’re kind of weaving it into different audiences. I saw a PR job in publishing, and because I loved reading as a kid, I thought it would be cool to work in a publishing house. I went right into stories without realising that eventually, I would be telling my own stories. It was so much fun, I loved, loved working and publishing. I got overworked though, like many creative industries, which eventually led to me being burnt out.

DAM: Would you say there was a moment for you where Writing and being an Author was something you felt you wanted – or needed to do?

YS: The moment for me was COVID. I was doing the publicity campaign for an author and I got an invitation for her to come to the Sydney Writers Festival. I was taking her around to different events and she had an event in Parramatta that day. I was exhausted because I was pregnant at the time, which no one knew.

“I remember being in the back of a taxi, going back to Milson’s Point, and I just started crying in the back of this taxi because my first thought was, ‘When is my brother going to see my child?’ I went from being able to see my family whenever I wanted to, to everything being shut for what felt like the absolute longest lockdown.”

yvonne sewankambo

That was tough, but then I started writing how I felt and I wrote about a sibling bond, and I was like, ‘Oh, that felt good, sort of letting it out’. Then I got home and I showed it to my husband. He looked at it and he said, ‘This actually feels like a kid’s book, it’s better than some of the stuff you’ve shown me’. And then I looked at it again and I just had this moment of sitting and looking at it – I was afraid to show it to anyone else but I wrote it because my brother inspired it. The thing with writing is that your passion for a subject will shine through the writing. The next question was, do I show it to someone? Do I show it to an agent? Because I was in publishing, I knew the process that went into it, especially a debut children’s author, a diverse debut children’s author who hasn’t been writing anything really. What would go into the pitch?

I needed to show that I could write more than just one. I always write stories that I have some connection to because I feel like I can tell those stories better. So the first one I wrote was, ‘First There Was Me, Then There Was You’. And then ‘Good Hair’, which came out first. ‘Good Hair’ came from my experiences with my hair. Growing up as a kid in Uganda, schools required some of the kids to cut their hair, like completely shaved. They say it’s “for maintenance” and to “keep you focused on school” because then you’re not playing with your hair, especially for girls. But it actually started during colonial times as a way to get rid of the ‘nappy hair’, it’s to make you lose some sense of identity. I always found it weird because it was only the black students. There’s a big Indian community in Uganda, but they weren’t required to cut their hair. I was like, hang on… They could grow their hair as long as they wanted, and some teachers would say it’s their culture. Basically, the rules didn’t apply to anyone who wasn’t dark skinned; it was for those who had ‘nappy hair’.

“As a kid, you’re growing up and you’re like, ‘Oh, is there something wrong with my hair?’, because you’re being told there’s something wrong with your hair without being directly told that.”

yvonne sewankambo

DAM: Absolutely, it’s interesting how these things can become so ingrained from the start.

YS: I remember when people would get to the end of high school, which is when you leave all the rules behind. There was this goal for a lot of the girls that because they now have the freedom, they would instantly grow out their hair and relax it because then you get that length, and that flow. That was a strange thing; everyone would look forward to it, which I always found weird. It’s like the minute you’re able to grow your hair, your first instinct is to relax it, put chemicals in it, break down the nappiness of it.

I left Uganda to finish high school in Canada and then started growing my hair. I think I relaxed it for a month, but then after I was like, ‘what is this?’ It’s like, why am I burning my scalp? This makes no sense. I just stopped and I’ve had my natural hair since. Nowadays, there’s this natural hair movement, which is really cool. There are more and more black women embracing their natural hair. So my experience writing ‘Good Hair’ came from that, especially in a lot of the magazines, my type of hair is not necessarily in there. If it is, it’s done a certain way or it has to be a specific kind of curly, not like the really hard, difficult to comb type of hair.

“I wrote ‘Good Hair’ thinking – if it makes a little kid out there feel like their hair is good enough, then it’s worth it… While the lead character is a black girl embracing her hair, you’ll notice a lot of the characters are a good mix because I feel like everyone, especially women, have their own hair issues.”

yvonne sewankambo

The lead of the book is a black girl, which was one of my big non-negotiables with my publisher. All the lead characters of my books have to be black. The thing with ‘Good Hair’ is that, while it is about the lead character as a black girl embracing her hair, you’ll notice a lot of the characters are a good mix because I feel like everyone, especially women, have their own hair issues. I wanted it to just be more open in that sense, allowing kids who feel different to embrace that.

DAM: That’s really great, we’re sure it has done so – actually tell us, how was Good Hair received?

YS: It actually ended up better than I expected, and even my friend said this is actually now a staple in our house. And it’s not from them shoving it down their kids’ throats because it’s mine – it’s from their kids actually asking to read it. What I like doing is creating books that transcend gender as well, which I’m absolutely grateful for because sometimes in children’s books, people like to categorise them as a ‘girl’s book’ or a ‘boy’s book’. A good book’s a good book. And if a kid wants to read it, they’ll read it. I think one of the highlights is when my son sees it, he yells, ‘it’s Mommy’s book!’ Even at daycare, because I gave it to his daycare as a gift, and they read it to the kids. I’ve done readings at some daycares, at libraries, and it’s just been nice seeing the kids ask questions. It was also shortlisted for Children’s Book Council of Australia, ‘Book of the Year’ Award in its category. And I was like, oh, I genuinely did not think that would happen but it was a nice surprise. That is like the best type of reception you could think of when you put something out there – everything that you think would go well, went well.

DAM: What was the process like being on the opposite end of publishing – pitching your own work this time?

YS: I signed a four-book deal with Walker Books. I sent it to different agents and then I met my current agent. We clicked. She loved the stories. She (Sarah McKenzie) saw the vision, and then from there, she sent it to the different publishers. In the end, there were two that were really interested.

“Shockingly they gave me a four-book deal. I was like, this never happens… Maybe it actually is good writing.” [laughs]

yvonne sewankambo

They said we want to do Good Hair first and First There Was Me, Then There Was You second which from a PR point of view, I understood because my ideas for three and four were very much in sync with First There Was Me, Then There Was You.

It made me realise that I actually wanted to do this full-time but I also don’t want to just be a children’s author – and I don’t mean to say that children’s authors are less than, I would just like to write across ages. I’m working on a novel which has taken me two years to write. I just like stories that cut across. For example, when people ask me what’s your favourite movie? I don’t have a specific answer. For me, a good movie is a good movie; if it’s a good cast and a good script, I will watch it. I can comfortably watch Fast and Furious, and I can comfortably watch an Oscar-winning, deep drama, and I will be entertained by both. So that’s why I want to write across genres because I feel like I have stories that kids would enjoy, and I have stories that I would enjoy as a grownup as well.

DAM: No matter the genre you are writing, what would you say are the biggest, common, central themes that you like to incorporate into your work?

YS: Culture and identity are very big ones for me. And identity could be in terms of your cultural background, your skin colour, your sexuality. I feel a lot of the stuff that I write is rooted in everyday experiences. I’ve got a friend with whom we exchange notes very often, and she made a comment, she’s like, ‘You love the chaos in the day-to-day. You love that a person isn’t just one thing. You love the complexities and the tension that is sort of in between different characters.’ Yes, and when I’m watching something I like or reading something I like, when you can see that there’s this weird internal fight that a character’s experiencing – I feel like that’s life. Nothing is this picture-perfect, cookie-cutter kind of moment. No one is that. So I like seeing that. I like writing that.

DAM: Tell us a bit about your latest release, ‘How My Family Says I Love You’?

YS: ‘How My Family Says, I Love You’ is my new book that’s just been released in Australia and New Zealand and will be in the US,Canada and Uganda in September. It’s essentially about different ways that families show love because growing up in many Ethnic families, my own as well, the feedback I’ve gotten from different people on different continents across different countries, they have the same shared experience in that. Their parents never said ‘I love you’ and they’ve never said ‘I love you’ to their parents either, because it was just this weird thing. But then we see it all the time in movies. You see people declaring their love for their parents, it’s almost as if it just rolls off the tongue so easily. I’d see it so often, and I just have these moments of ‘do my parents love me?’ But then you know they do, but you’re like, do you really know? They’ve never actually said it, but you even sit at the dining table, and you can’t even ask the question because it’s a weird question to ask, but you also feel it would just change the dynamic. You’re like, what if they say they don’t? Which is stupid because if you think about it now it’s like, well, they do. But they do it through their actions. Those are the common stories from many people I’d ask. I’d be like, okay, how would they show love? And it’s like, oh – you sit down, they bring you food, they make sure you have a roof over your head. They make sure you never see them struggle trying to get tuition for whatever school you want to go to. They want to make sure you have the best experience and they never want to make you feel like you’re a burden. Those little things that they did and you realise that sometimes when someone says I love you, they don’t necessarily mean it. But then there’s this weight that goes into someone saying it and that need for validation. So I decided to write about it because I wanted to show all these little kids out there who don’t actually hear it, that you need to look for it. You need to look for the ways that they’re actually doing it. They might not say it, but they’re showing you in many different ways. And then for people who get to hear it, showing them that you might hear it, but if it doesn’t necessarily come with the actions, then how strong is it? So I hope there will be happier kids out there when they realise that actually, you are loved, you’re just loved in a different way.

“I decided to write about it [How My Family Says, I Love You] because I wanted to show all these little kids out there who don’t actually hear it, that you need to look for it. You need to look for the ways that they’re actually saying it.”

yvonne sewankambo

DAM: That’s a beautiful and very relevant message to represent, especially in Australia where everyone comes from Multicultural families. If you were to give a word of advice to people out there, maybe in the position you were before, who are unsure if their work is good but they have a passion to create, what would you say?

YS: Two things. I think from what I’ve created from my books and my work, don’t be afraid to be yourself. Don’t choose to be someone else, that’s not gonna get you anywhere. It might get you somewhere, but there’ll be a point where you actually miss your old self, miss bits and pieces of yourself and you want to go back to that. Which is why, with my stories, it’s putting bits of myself in there and if someone doesn’t like it, then it’s not for them. You cannot please everyone. So don’t be afraid to be your best, authentic self. And then the other is, don’t be afraid to fail. It’s scary putting yourself out there, especially as a creative, everyone will have an opinion about your piece of work. If it’s right for you, everything else will follow.

“You cannot please everyone. So don’t be afraid to be your best, authentic self. And don’t be afraid to fail. It’s scary putting yourself out there, especially as a creative, everyone will have an opinion about your piece of work. If it’s right for you, everything else will follow.”

yvonne sewankambo

.

.

Find more on Yvonne & her books here:

Website/Books: https://www.yvonnesewankambo.com/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/ysewankambo/