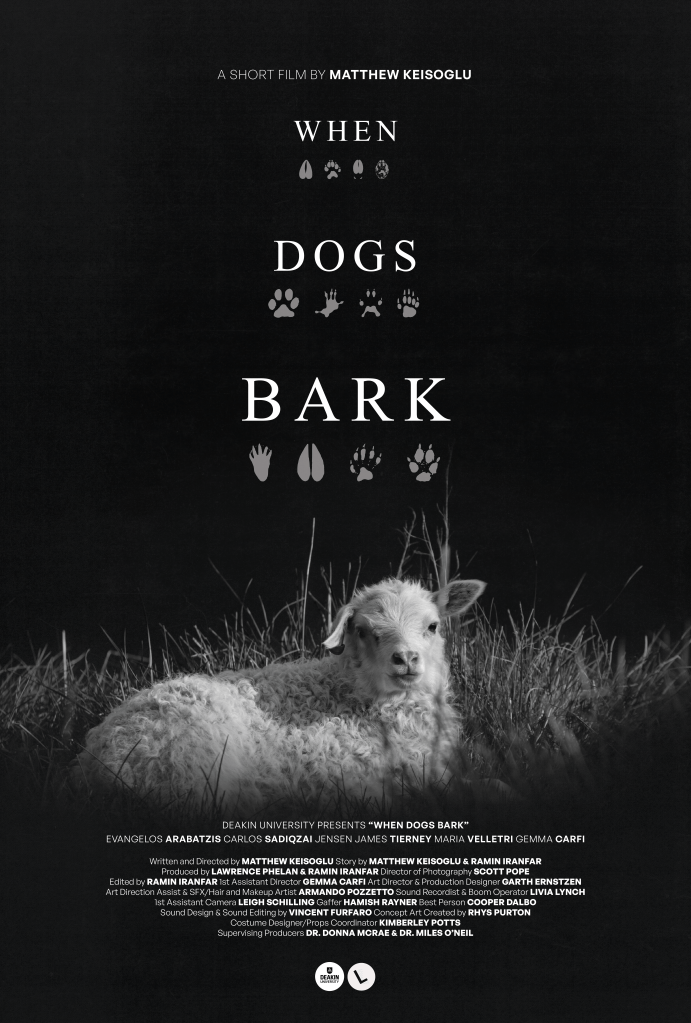

DAM: Matthew Keisoglu is an Armenian-Australian filmmaker and the Founder and Festival Director of the Multicultural Mental Health Film Festival. A descendant of genocide survivors, this is an important, family history – and one shared by many across the world in the past and currently – that Matthew often layers into the stories and films he creates. Infusing Horror with culture, Matthew’s latest film When Dogs Bark, follows the relationship of a father, haunted by memories of the past, and his son, who inherits this trauma, although he cannot relate to it. Directed by Keisoglu, the film was co-written by Keisoglu and Ramin Iranfar and produced by Iranfar and Lawrence Phelan, with cinematography by Scott Pope.

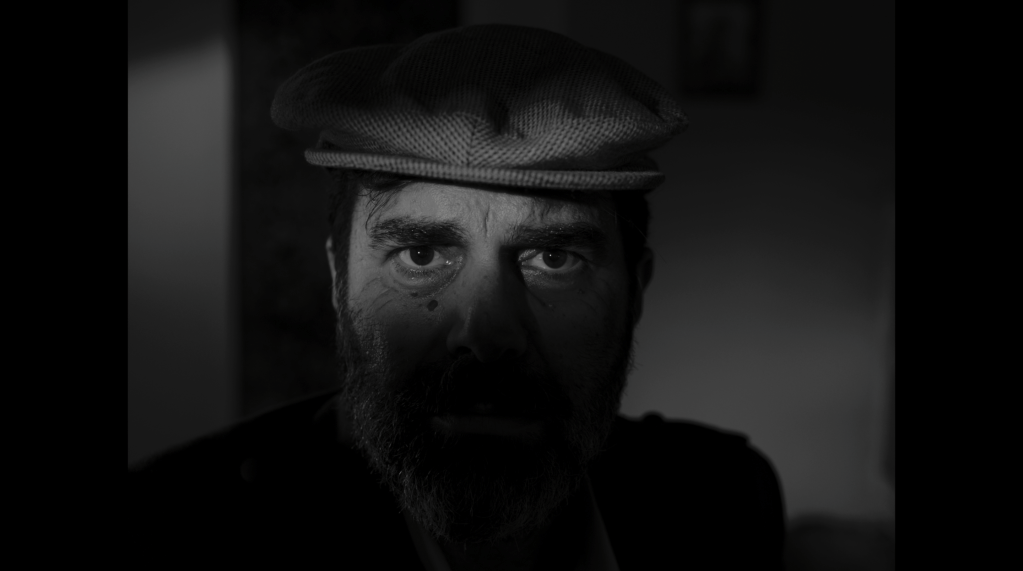

After watching the film, it’s clear to see how genocide, war and trauma can severely affect people and families for generations – even beyond those who experienced it first hand. The grief and pain of such tragedies cannot be forgotten, but finding ways for it not to consume us is important in finding any sort of resolve in order to move forward. Actors Evangelos Arabtzis and Carlos Sadiqzai believably play a father and son at odds with each other, who have clearly grown up in different circumstances. The cinematography, production and costume design, provide authenticity while the Horror creates the uncomfortableness needed to find empathy in the very real and relevant trauma of this story. We speak to Matthew on how this film came together as well as delving deep into its central themes and what he hopes audiences will take away from it.

‘After his father’s lambs are brutally slaughtered, an intellectual son returns to his widowed father’s remote shack, confronting haunting signs of violence his father fears is returning.’

DAM: What inspired you to write this short film alongside co-writer Ramin Iranfar?

MK: The film was made as part of my Master of Arts at Deakin University. Before that, I had made two horror shorts—one during my Bachelor’s and another in my Honours—both exploring horror through sociocultural aspects of my Armenian heritage.

I met Ramin at Deakin in 2016, and we started working closely together in 2021 when he produced and edited my Honours short, His Trembling Hands: An Immigrant Ghost Story. That film portrayed Turkish migrants as ghostly, spectral figures—detached, unanchored, and yearning for worlds they once knew. Ramin isn’t a horror fan like me, but he was attracted to its cultural core. The same thing happened with When Dogs Bark.

I started writing this film around 2023, while beginning my Master’s, during which I researched genocide and horror cinema. Most of my writing was auto-ethnographic, drawing on personal experiences and inherited memories of the Armenian genocide. I aimed to ground the horror in metaphor and atmosphere, while Ramin pushed me towards human detail and nuance—such as how a character shaves, dresses, and what that reveals about their inner struggle.

“Most of my writing draws on personal experiences and inherited memories of the Armenian genocide. I aimed to ground the horror in metaphor and atmosphere, while Ramin (Co-writer) pushed me to focus on the human detail and nuance, not just horror, whether in culture or genre.”

matthew keisoglu

I wrote the script, but Ramin’s input was crucial. He helped me keep my focus on the human element, not just horror, whether in culture or genre. At its core, When Dogs Bark is about cultural trauma, genocide, and partly, the migrant experience—filtered through horror, but always rooted in humanity.

“At its core, When Dogs Bark is about cultural trauma, genocide, and partly, the migrant experience—filtered through horror, but always rooted in humanity.”

Matthew Keisoglu

DAM: How does your cultural background influence the work you make?

MK: As an Armenian, everything about this film originates from my culture. The inspiration came from Azerbaijan’s invasion of Artsakh in 2022, a region many see as historically Armenian. I won’t delve into the politics here, but what I witnessed — famine, blockades, and violence — struck a deep chord. As Armenians, we recognise these cycles of violence well; they echo the wounds of genocide.

At the same time, I didn’t want to make When Dogs Bark merely an “Armenian film.” I was concerned that doing so might limit its relatability or scope for other cultures. I even thought about working with Armenian actors in Australia, but it didn’t feel right.

It seemed too confined, too narrow. My heritage and culture are the roots of the film, the reason it exists, but they don’t completely define it. You’ll notice Armenian motifs throughout: the pomegranate, Orthodox Christian imagery, and the traditional Father/Son relationship. Armenians will recognise these immediately. But I hope audiences from other backgrounds will see themselves in these themes too — in the trauma, the silence, and the inheritance of memory that crosses borders.

“I hope audiences from other backgrounds will see themselves in these themes too — in the trauma, the silence, and the inheritance of memory that crosses borders.”

Matthew Keisoglu

DAM: Tell us about your decision to have the film be in the Greek language?

MK: Choosing Greek felt natural. Our cast has Greek roots, and because of the Armenian Genocide, parts of my own family history are erased, so that loss has shaped how I see identity. Greeks, like Armenians, understand survival and kinship — both cultures scarred by genocide, displacement, and the struggle to keep their culture alive in diaspora. The film had to come from within that space.

In When Dogs Bark, the Father speaks both Greek and English, while the Son speaks only English. That divide reflects the reality for many migrant families: survivors cling to their mother tongue as a vessel for memory and grief, while the next generation grows up more distant, speaking only the language of their new home. The Son’s English serves as a metaphor for that divide, representing what is remembered, what is lost, and what cannot be fully understood across generations.

“In When Dogs Bark, the Father speaks both Greek and English, while the Son speaks only English. That divide reflects the reality for many migrant families: survivors cling to their mother tongue as a vessel for memory and grief, while the next generation grows up more distant, speaking only the language of their new home.”

Matthew Keisoglu

This captures the essence of father–son relationships and inherited trauma. The Father, tied to memory, bears the weight of history. The Son, wanting to be disconnected from that world, dismisses it — but trauma doesn’t disappear just because it’s ignored. Denial only risks repeating what was endured before.

The turning point came when Greek-Australian actor Evangelos Arabatzis auditioned for the role of the Father. His presence carried both tragedy and pride, and from that moment, the film had to be in Greek. Fellow Greek actor Carlos Sadiqzai completed the dynamic as the Son. Though the dialogue shifts between Greek and English, the story speaks universally — to Armenians, Palestinians, Jews, Ukrainians, Bosnians, Rwandans, and Indigenous peoples whose histories still carry the weight of violence.

DAM: Was the Black&White colour & 4:3 aspect ratio a stylistic choice or is there another reason behind this decision?

MK: I shoot most of my films in black and white and 4:3, so for When Dogs Bark, it wasn’t just a stylistic choice but driven by influence and necessity.

I’ve always been drawn to slow cinema: films like Robert Eggers’ The Witch, Henrik Malyan’s Life Triumphs, Nuri Ceylan’s Cocoon, Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Memoria, and Béla Tarr’s The Turin Horse. The use of long takes, minimal editing, and 4:3 framing strips away distractions and forces you to confront raw human emotion. That cinematic language was essential for a farmland horror shaped by faith, cultural trauma, and generational divides.

The choice also carried cultural weight. I was deeply influenced by Armen T. Marsoobian’s Reimagining a Lost Armenian Home, with its fragile black-and-white photographs of an Armenian family before and after 1915. Those images guided everything — costumes, framing, even how actors’ faces sat in the light.

So, while black and white and 4:3 connect the film to a cinematic lineage I admire, they also act as a memorial gesture — evoking memory, testimony, and loss. For me, it wasn’t about being “arthouse,” but about using a form strong enough to hold the weight of trauma.

“While black and white and 4:3 connect the film to a cinematic lineage I admire, they also act as a memorial gesture — evoking memory, testimony, and loss.”

Matthew Keisoglu

DAM: How did you go about bringing this story to life?

MK: Because When Dogs Bark was created during my Master of Arts at Deakin University, the film was produced alongside my written thesis. I spent months engaging with theorists who shaped my thinking: Derrida’s hauntology, Andreas Bandak on repetition and haunting, Aleida Assmann on cultural memory, Uğur Ümit Üngör on memorialisation, as well as Linnie Blake and Leshu Torchin on trauma and testimony in genocide cinema. Their ideas gave me the language to articulate what I already felt — that genocide doesn’t end but lingers as memory, shaping cultures and communities.

Just as meaningful were the personal conversations with my parents and within my community. The stories of silence, loss, and resilience I inherited became the film’s emotional anchor. From there, it was about building a team: my longtime collaborator Scott Pope as cinematographer, and others who gave their time and talent, some volunteering, others working for modest pay. While the film was self-funded, Deakin also provided equipment and resources.

The process itself was absolutely relentless — long nights, multiple cuts, endless problem-solving — but through that grind, the film took shape. The film is ultimately a way to honour my heritage, my parents, and the Armenian community, while creating something that speaks more broadly about genocide, mass violence, and cultural trauma.

“The film is ultimately a way to honour my heritage, my parents, and the Armenian community, while creating something that speaks more broadly about genocide, mass violence, and cultural trauma.”

Matthew Keisoglu

DAM: Where in Australia did you film/what was it like filming on location there?

MK: We filmed When Dogs Bark in Cobaw, Victoria, inside an old settler’s cottage I found online. Getting there was an adventure: down one dirt road, then another, through a private farm, and finally up a hill before you even saw the house. It was completely cut off — no water, toilets, or electricity — so we relied on a generator, and because our gaffer, Hamish, was the best of the best, nothing went wrong!

Most of us stayed in an Airbnb 15 minutes away, while a few crew camped in an RV nearby. It felt like a mix of camping and film school — night shoots until 3 am, endless Red Bulls and coffees to keep me alive. The location itself became part of the film. The cottage, once used by Irish settlers, with its warped timber and gangly trees, reminded me of Sam Raimi’s Evil Dead cabin, that same eerie isolation.

One shot of the Son walking toward the house I framed as a nod to Andrew Wyeth’s painting Christina’s World, capturing human fragility against a vast, lonely landscape. Our production designer, Garth, and SFX/makeup/production assistant, Armanda, transformed the cottage into the Father’s shack by layering it with ethnic culture, age, and trauma until it felt genuinely haunted.

At one point, during a 3 am shoot on a hill, we heard dogs barking in the pitch black — unseen, but we knew they were close to us. It felt like we’d stepped into the world of the film itself.

“It felt like a mix of camping and film school — night shoots until 3 am, endless Red Bulls and coffees to keep me alive. The cottage was once used by Irish settlers… At one point, we heard dogs barking in the pitch black — unseen, but we knew they were close to us. It felt like we’d stepped into the world of the film itself.”

Matthew Keisoglu

DAM: What’s one of the biggest lessons you’ve learned through making this?

MK: I needed people to help me. What got me through this film was the people around me. It was endless visits to Ramin’s house, long nights with Vincent on sound, Lawrence’s, our producer’s notes, and my Deakin supervisors’ guidance all sustained me while I was also running the Multicultural Mental Health Film Festival and caring for my dad. Some days it felt impossible, but those moments of collaboration made it feel achievable. I’ve always preferred working alone, worried that others wouldn’t understand my vision. But on this film, I realised that wasn’t the case.

When the film was finally finished, screening it to the cast, crew, and family meant everything to me. It’s daunting to have your work on display, but it only showed how much people supported me and my vision.

DAM: What would you say is the most rewarding thing about creating work that not only entertains, but informs and resonates with audiences on a deeper subject matter?

MK: For me, the most rewarding part is discovering how horror can become an accessible way to discuss cultural trauma. That’s something I explored in my thesis — the idea that horror cinema has a unique language, one that can translate the weight of cultural memory, genocide, and intergenerational fear into something audiences can sit with and understand through genre tropes. It’s why I love the horror genre. For those who don’t know, Godzilla (1954) isn’t just a film about a huge monster wrecking stuff.

With When Dogs Bark, the horror isn’t in a jump scare or a monster, necessarily. It’s in the silence between father and son, in the barking of unseen dogs, marching soldiers, and the fear of a man who’s been entrenched by the past. These elements function as horror symbols, despite originating from a cultural context. Horror enables you to express grief, displacement, and memory in a way that people can easily understand and connect with without looking away. It unsettles, but it also fosters empathy. That’s the reward for me.

When someone says the film unsettled them, or that it lingered, it means the story didn’t just entertain but hit something deeper. It meant that the film and the horror genre had done their job as both art and testimony, making the weight of trauma felt but in a way audiences could hold onto.

“The horror isn’t in a jump scare or a monster… It’s in the silence between father and son, in the barking of unseen dogs, marching soldiers, and the fear of a man who’s been entrenched by the past. Horror enables you to express grief, displacement, and memory in a way that people can easily understand and connect with without looking away. It unsettles, but it also fosters empathy.”

Matthew Keisoglu

DAM: Horror films are often scary for the viewer – but what are they like actually making them behind the scenes?

MK: Horror films are strange to make because, while they scare audiences, behind the scenes, they’re all about timing, problem-solving, and metaphor. For me, it’s never about the cheap scare — every unsettling image must mean something.

In When Dogs Bark, the Father’s discovery of lamb heads serves a purpose beyond shock. In Armenian Catholic culture, lambs symbolise innocence, so seeing them butchered becomes a chilling metaphor for genocide — the destruction of the most defenceless. As mentioned, horror isn’t just about fear. It’s a way of turning cultural trauma into digestible symbols, giving audiences a form they can sit with, process, and understand. With the lambs, it’s easier to make people afraid of things they already recognise or can link together.

The reality of filming, though, was absurd. Ramin drove over an hour with the lamb heads (which are Persian delicacies) packed in an esky, then had to cart them back and dump them in his own bin after the shoot. That’s the paradox of horror filmmaking — what looks haunting on screen often comes from surreal, exhausting logistics.

DAM: What do you hope audiences will take away from ‘When Dogs Bark’?

MK: I don’t want audiences to leave When Dogs Bark with a tidy resolution — because trauma doesn’t resolve neatly, nor does the film. It’s up to you to interpret what happens at the end.

If the film succeeds, people from all backgrounds — whether Armenian, Greek, Palestinian, Jewish, Ukrainian, Indigenous, or otherwise — will recognise aspects of their own history in it. I want them to feel the universal nature of inherited trauma, and to understand that ignoring it doesn’t make it go away. It lingers, reshapes itself, and demands to be faced. Trauma materialises. When people watch the film, they’ll understand what I mean by that.

More than anything, I hope viewers leave with empathy. Horror can unsettle, but it can also open one up. I hope they grasp the reality of genocide and come to terms with it. If When Dogs Bark unsettles and moves them equally, then I’ll feel I’ve done my job.

“If the film succeeds, people from all backgrounds — whether Armenian, Greek, Palestinian, Jewish, Ukrainian, Indigenous, or otherwise — will recognise aspects of their own history in it. I want them to feel the universal nature of inherited trauma, and to understand that ignoring it doesn’t make it go away. It lingers, reshapes itself, and demands to be faced. More than anything, I hope viewers leave with empathy.”

Matthew Keisoglu

.

.

Find more on Matthew & When Dogs Bark here:

When Dogs Bark Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/whendogsbarkfilm/

Matthew Keisoglu on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/_keisomfilms/

Matthew Keisoglu’s Website & Film Links: https://www.liinks.co/keisomfilms

Multicultural Mental Health Film Festival: https://www.mhfa.org.au/MulticulturalMentalHealthFilmFestival